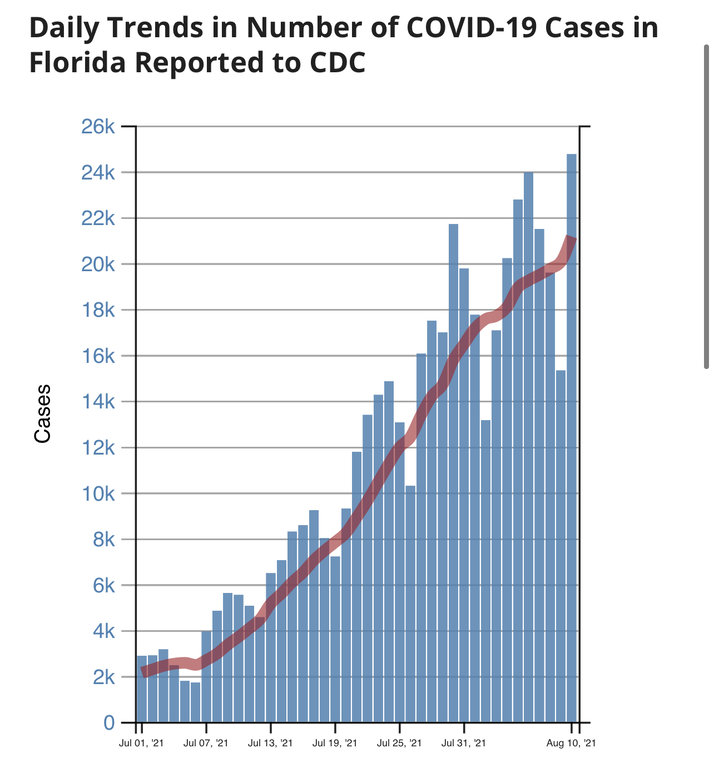

I struggle to think of anything in the universe less likely to happen that does not defy known laws of physics or any defining hypotheses from other fields of science.At this point Florida should shut down for 30 days. Close all the theme parks, close the beaches, restrict highway and air traffic into and out of the state. Do a New Zealand style lockdown and pay Floridians to do it. Nobody goes outside of their homes, save for emergency personnel and very essential goods.

-

The new WDWMAGIC iOS app is here!

Stay up to date with the latest Disney news, photos, and discussions right from your iPhone. The app is free to download and gives you quick access to news articles, forums, photo galleries, park hours, weather and Lightning Lane pricing. Learn More -

Welcome to the WDWMAGIC.COM Forums!

Please take a look around, and feel free to sign up and join the community.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Coronavirus and Walt Disney World general discussion

- Thread starter Parker in NYC

- Start date

-

- Tags

- coronavirus covid covid-19

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Andrew C

You know what's funny?

I’ll take things that are not possible for 100, Alex.Honestly if we did a worldwide 30 day lockdown we would all but eradicate it (and other viruses)

aww. I miss Alex.

Gringrinngghost

Well-Known Member

Protective Allergy Parent upset with a possibility of peanut contamination should not be upset with another preventative method that can easily affect many others if not in place.

CosmicRays

Well-Known Member

Vaccines, Vaccines, Vaccines. This country never really locked down the first time around. Not to mention the infrastructure isnt there for a true stay at home lockdown. The only way to fight it is vaccinating as many as we can.

Chomama

Well-Known Member

My friend is an oncologist at our university hospital. They are receiving a booster tomorrow.Interestingly someone I know just had third shot. First shot produced zero antibodies. 2nd did but they went for third. (Part of a study)

GimpYancIent

Well-Known Member

I personally do not believe any data / statistics or information officially released by the Chinese authorities. Stories corroborated by multiple international news sources like AP / UPI have reliability but come out slow. Fortunately WDW dealing w COVID19 is not impacted by China virus controls imposed on its citizens.China has a lot of people , currently does not allow in the MRNA vaccines, so the VE is much lower there. But what they have better than anywhere else is controls to try to limit spread into and within their country.

If the west achieves local herd immunity we will need to see what controls we will need to minimize new variants from entering and spreading within the country. China is an example of a very heavy set of controls . ( Though with a poorer vaccine as a baseline to work with )

Delta is a challenge for China even with the strong controls, but their reported cases are still low compared to the west ( at this time). But it does show that controls are just one part in the battle against covid.

Whether anywhere else in the world could tolerate that level controls to minimize spread is doubtful in more liberal western societies.

Delta variant challenges China's costly lockdown strategy

The delta variant is challenging China’s costly strategy of isolating cities, prompting warnings that Chinese leaders who were confident they could keep out the coronavirus need a less disruptive approach.apnews.com

Last edited:

ArmoredRodent

Well-Known Member

Um, both? After all, negative vs. positive rights is mostly a philosophical distinction, not a constitutional/legal one. This does not mean that there's anything "negative" about it; it's just a fancy way of saying the government can't do something because the Constitution bars it from doing so, like the First Amendment's protection of expression, religion, peaceful assembly, etc. While a "positive" right forces the government to do something it may not want to do. And the Constitution clearly includes both. Even the Bill of Rights (first ten Amendments to the Constitution) does, too.Depends on if you see the Constitution as positive or negative rights.

It's true that most of the rights in the Constitution are negative rights. Example from the recent District Court decision on whether cruise ships can require documentation of vaccination: the Florida rule that cruise lines can't demand your vaccine record card, but can ask if you've been vaccinated, violates the First Amendment's express negative right (incorporated by the 14th Amendment against the States) that government "shall make no law respecting" speech. The First Amendment says government shall not compel (or block) speech based on its content, so if you have to look at what was said (or done) to know whether the law has been broken or not, it very likely will violate the First Amendment. The Florida rule prohibits information being presented in writing (ironically, by a government agency) while permitting the same content from being spoken, so was based on content and subject to a successful negative right challenge.

But then there is the Sixth Amendment's power to compel the government to provide criminal defense counsel and speedy trials, which is a positive right. And tons of things that have elements of both negative and positive (which tend to be in "penumbral" rights found in interpretations of language, rather than the common understanding of clear and specific constitutional language), like the right to privacy, marriage or nondiscrimination. As a result, in legal interpretation these days, the distinction is more often phrased whether the asserted right comes from the text of the Constitution or an interpretation of it; textual rights tend to be more persuasive to most judges, simply because they don't require as much research to see how they've been interpreted in the past. IOW, we argue more about "positive," non-textual rights because it isn't clear if they are just confirmation bias or normative (what the law "should be" instead of what it "is"), while it's pretty clear where negative "shall not" prohibitions start the constitutional journey. But under the Sixth Amendment, if you get arrested, you get rights against the government. It's right there in the Bill of Rights:

"In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury ..., and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor [IOW, subpoenas], and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence." Hence, Miranda warnings when you're arrested, to be sure you know your rights. (Yes, I know Ernesto Miranda himself was supposedly a scumbag but the genius of the system is that even scumbags get rights. Both negative and positive.)

Club34

Well-Known Member

Pride, rugged individualism, etc during a pandemic can be/will be catastrophic.He messed up and seriously got caught with his pants down. So he doubled down hoping things would get better in the meantime so he wouldnt have to say he was even a smidgen wrong. I suppose he is also trying to get the Trump base to fuel his future ambitions. In their eyes, admitting that you are wrong is admitting failure.

And then it's WAY WAY too long to get back to normal by end of the year or early 2022...

End of the year? I hope you are right but I fear you are very wrong. There are too many things going wrong with both the virus and the humans for this to just go back to normal. I am the dumbest person on the forum but I think the ship has sailed. New strategies are necessary and for that, you will need new (I mean really new) leadership and you are not going to get it which is ironic because that is what brought us here in the first place. If this sounds like a paradox, it's because it is.

Most likely: Everyone will have to think outside the box. Everyone will have to do things they don't want to do. The plan is dead in the water because too many will not work together to literally save their lives and most people can't think outside the box (I am probably in one or more of those categories- owning my own "stuff" here). There is your new ground zero. Sorry.

DisneyFan32

Well-Known Member

- In the Parks

- Yes

Perhaps early 2022 as things may go back to normal as zero cases but end of the year is still possible as maybe.Pride, rugged individualism, etc during a pandemic can be/will be catastrophic.

End of the year? I hope you are right but I fear you are very wrong. There are too many things going wrong with both the virus and the humans for this to just go back to normal. I am the dumbest person on the forum but I think the ship has sailed. New strategies are necessary and for that, you will need new (I mean really new) leadership and you are not going to get it which is ironic because that is what brought us here in the first place. If this sounds like a paradox, it's because it is.

Most likely: Everyone will have to think outside the box. Everyone will have to do things they don't want to do. The plan is dead in the water because too many will not work together to literally save their lives and most people can't think outside the box (I am probably in one or more of those categories- owning my own "stuff" here). There is your new ground zero. Sorry.

Epct82

Active Member

FTFYHonestly if we did a worldwide 30 day lockdown we would all be in Great Depression 2.0 by December.

DisneyCane

Well-Known Member

Honestly if we did a worldwide 30 day lockdown we would all but eradicate it (and other viruses)

Not only great depression 2.0 but at least tens of millions would starve to death as the type of lockdown needed would require no contact at all outside of your household. There isn't enough food available for everyone on earth to have a 30 day supply.FTFY

DisneyCane

Well-Known Member

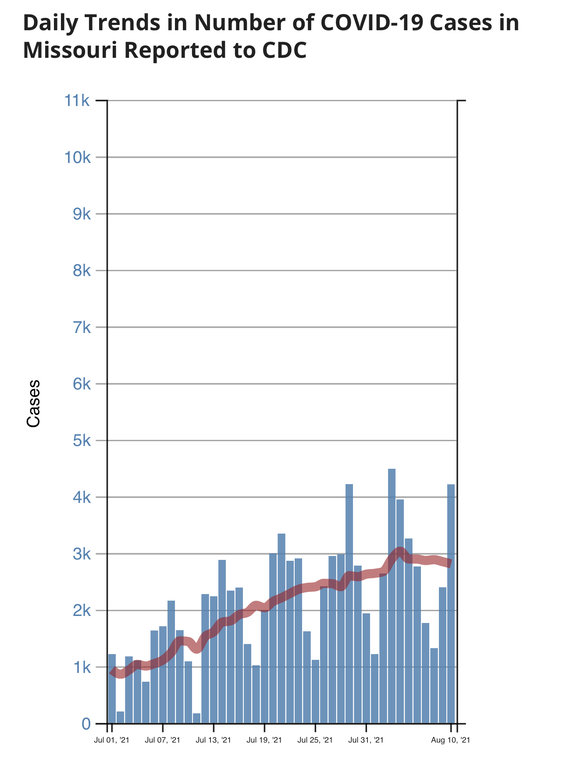

I'm still expecting this wave to peak in FL around 8/21 +/- a couple of days based on the UK and India followed by 5 to 6 weeks to come back down to June levels.Can we please stop with the Florida needs to lock down nonsense?! LOCK DOWNS DO NOT WORK. Even closing businesses for 30 days would be devastating for a vast

majority of small businesses.

Circumstances are a lot different than they were in the spring of 2020. We have a weapon against the virus. The vaccines are working! Florida will get through this wave just like they have in the past.

More vaccinations won't help this wave at this point but will prevent future waves of there are enough of them.

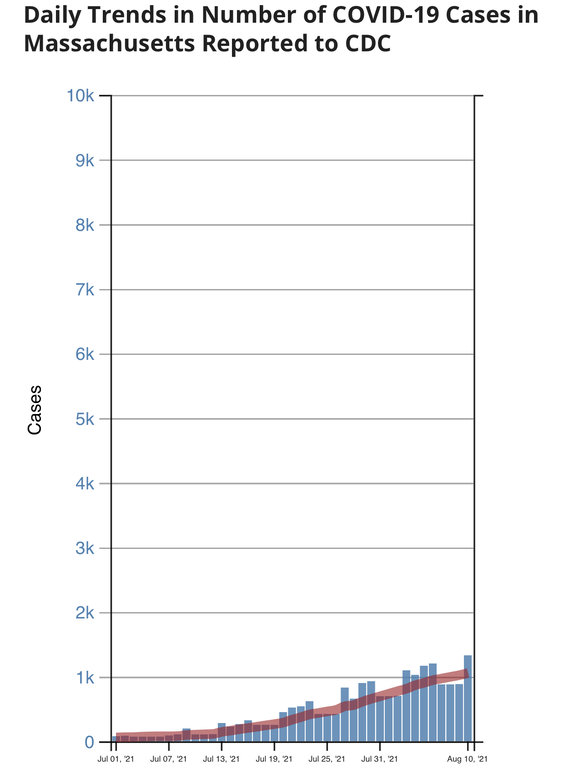

I realize "the numbers" in FL are high right now but the low and moderate spread counties are almost gone Nationwide even in very highly vaccinated States like Vermont and Massachusetts. I think it's a mistake to not expect spikes in the places where the Governors are great and "follow the science" and the residents "do the right thing."

oceanbreeze77

Well-Known Member

it is absolutely insane (that its happening) that states are building field hospitals again.....SMH.

Thanks for the history lesson but for anti vaxers including ones who got and recovered from covid and think they are now immune - be a responsible person and just get the shot .Um, both? After all, negative vs. positive rights is mostly a philosophical distinction, not a constitutional/legal one. This does not mean that there's anything "negative" about it; it's just a fancy way of saying the government can't do something because the Constitution bars it from doing so, like the First Amendment's protection of expression, religion, peaceful assembly, etc. While a "positive" right forces the government to do something it may not want to do. And the Constitution clearly includes both. Even the Bill of Rights (first ten Amendments to the Constitution) does, too.

It's true that most of the rights in the Constitution are negative rights. Example from the recent District Court decision on whether cruise ships can require documentation of vaccination: the Florida rule that cruise lines can't demand your vaccine record card, but can ask if you've been vaccinated, violates the First Amendment's express negative right (incorporated by the 14th Amendment against the States) that government "shall make no law respecting" speech. The First Amendment says government shall not compel (or block) speech based on its content, so if you have to look at what was said (or done) to know whether the law has been broken or not, it very likely will violate the First Amendment. The Florida rule prohibits information being presented in writing (ironically, by a government agency) while permitting the same content from being spoken, so was based on content and subject to a successful negative right challenge.

But then there is the Sixth Amendment's power to compel the government to provide criminal defense counsel and speedy trials, which is a positive right. And tons of things that have elements of both negative and positive (which tend to be in "penumbral" rights found in interpretations of language, rather than the common understanding of clear and specific constitutional language), like the right to privacy, marriage or nondiscrimination. As a result, in legal interpretation these days, the distinction is more often phrased whether the asserted right comes from the text of the Constitution or an interpretation of it; textual rights tend to be more persuasive to most judges, simply because they don't require as much research to see how they've been interpreted in the past. IOW, we argue more about "positive," non-textual rights because it isn't clear if they are just confirmation bias or normative (what the law "should be" instead of what it "is"), while it's pretty clear where negative "shall not" prohibitions start the constitutional journey. But under the Sixth Amendment, if you get arrested, you get rights against the government. It's right there in the Bill of Rights:

"In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury ..., and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor [IOW, subpoenas], and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence." Hence, Miranda warnings when you're arrested, to be sure you know your rights. (Yes, I know Ernesto Miranda himself was supposedly a scumbag but the genius of the system is that even scumbags get rights. Both negative and positive.)

DonniePeverley

Well-Known Member

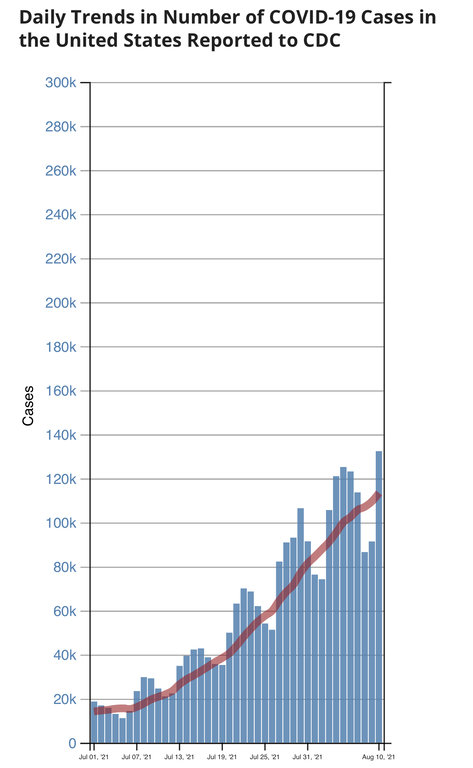

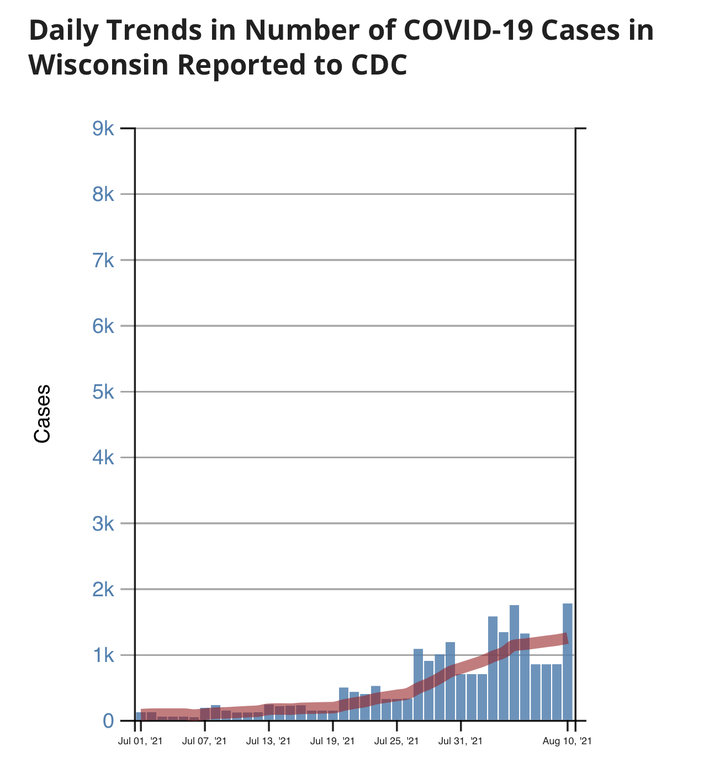

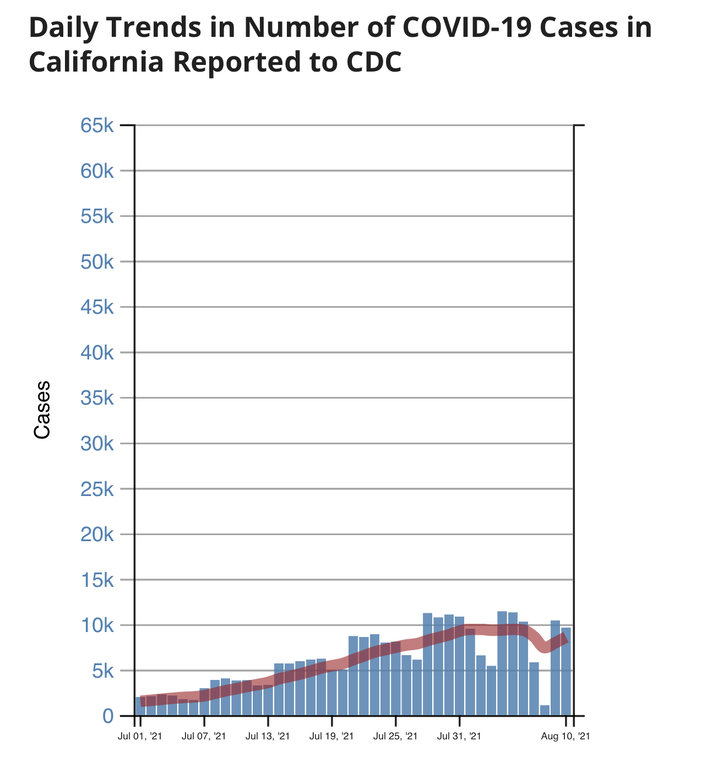

I'm still expecting this wave to peak in FL around 8/21 +/- a couple of days based on the UK and India followed by 5 to 6 weeks to come back down to June levels.

More vaccinations won't help this wave at this point but will prevent future waves of there are enough of them.

I realize "the numbers" in FL are high right now but the low and moderate spread counties are almost gone Nationwide even in very highly vaccinated States like Vermont and Massachusetts. I think it's a mistake to not expect spikes in the places where the Governors are great and "follow the science" and the residents "do the right thing."

Utter nonsense. Based on nothing. The rates in the UK are also creeping back up.

The whole scenario is really depressing - feels like we are back to square one to where we were last year looking at the rates.

Thanks for the history lesson but for anti vaxers including ones who got and recovered from covid and think they are now immune - be a responsible person and just get the shot .

It is so wild that the opposite has seem to be true. I did not investigate but I know there was at least a report saying that there was a percentage trend that those who had it before will actually more likely to get it again through Delta.

Patcheslee

Well-Known Member

The closest we had in our county in Indiana was the sgaybat home order. Yes it shut down restaurants and the like. But when you're community is made up of 70% manufacturing or farming it does very little good.Can we please stop with the Florida needs to lock down nonsense?! LOCK DOWNS DO NOT WORK. Even closing businesses for 30 days would be devastating for a vast

majority of small businesses.

Circumstances are a lot different than they were in the spring of 2020. We have a weapon against the virus. The vaccines are working! Florida will get through this wave just like they have in the past.

Don’t want to jinx it but we are now halfway through a week and the United States, including most states appear to be plateauing. This includes Florida, that may mean we are just about at peak for this wave. What’s fascinating is that places in the Midwest and Northeast where the current wave started later then Florida are also plateauing at the same time.

In regards to Coronavirus and WDW, it would probably be part of the Q&A of Wall Street directed to CEO Chapek when TWDC releases their Q3 company earnings report with Wall Street on a conference call this afternoon after the stock market close. Investors are expecting ( and betting ) on a big improvement compared to Q3 of last year which translates into helping fuel the record setting Dow Jones Industrials. The bulls are running and I'm in it for the long-term!

Last edited:

DonniePeverley

Well-Known Member

Don’t want to jinx it but we are now halfway through a week and the United States, including most states appear to be plateauing. This includes Florida, that may mean we are just about at peak for this wave. What’s fascinating is that places in the Midwest and Northeast where the current wave started later then Florida are also plateauing at the same time.

If you think that is a plateau i suggest you are wishful thinking.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Register on WDWMAGIC. This sidebar will go away, and you'll see fewer ads.