As recently reported by WDWMAGIC.COM:

Understandably, many want to know how much of this $60B will go to Walt Disney World (WDW).

During a shareholder's meeting on April 3, Disney CEO Bob Iger stated:

"Invest" is somewhat vague. Is this total capital expenditures or new investment?

Quoting from Investopedia:

Company officers often use the terms "investment" and "capex" interchangeably. Disney’s more recent statements regarding the $60B specifically references capex. Presumably, the $17B mentioned by Iger is total capex.

So what does $17B of capex buy us at WDW?

Capex is the purchase of an asset that will benefit a company for several years. Capex can be lumped into two broad categories, investment (or growth) and maintenance.

Disney replacing an old bus with a new bus can be thought of as maintenance capex. Disney adding a new bus to increase the size of its fleet can be thought of as growth capex.

When Disney buys that bus, its purchase price does not impact profit immediately. Instead, the cost of the purchase is spread out over the number of years it will be used. This is called "depreciation". It's this depreciation that impacts profit.

Let's say that a Disney bus costs $500K and Disney intends to keep that bus for 10 years. That $500K does not reduce profit by $500K the year it is purchased. Instead, that bus affects profit for 10 years by $50K each year in the form of depreciation. (Disney uses the straight-line method to depreciate assets.) Once that bus exceeds its useful life, it should be replaced with a new bus. This is especially true at WDW where Guests expect (and pay for) high standards.

Without detailed disclosures, a rule-of-thumb is to estimate maintenance capex to be equal to depreciation. Amounts spent below depreciation are (or should be) for maintenance. Amounts spent above depreciation are for growth (or investment).

Since the $17B appears to include both maintenance and growth capex, we have to understand how much Disney spends on maintenance capex in order to calculate how much they have left for growth capex.

During the most recently completed fiscal year (2022), domestic P&R depreciation is $1.68B. Overwhelmingly, this consists of depreciation from WDW, Disneyland Resort (DLR), Disney Cruise Line (DCL), and Disney Vacation Club (DVC).

Historically, roughly 80% of domestic P&R depreciation was associated with WDW’s massive 25,000 acre facility. With three large cruise ships added, and another two on the way, that percentage is changing. Still, the change is not particularly great. For example, the Disney Wish went into service earlier this year. With a rumored cost of $1B and Disney’s straight line depreciation method taking this down to $150M (i.e. 15%) in 30 years (a standard approach to depreciate large vessels), the Disney Wish adds about $28M in depreciation per year. With total domestic P&R depreciation at $1.68B in 2022, that’s a 1.7% increase. Given recent additions to WDW also adding to depreciation, last year’s WDW depreciation probably is around $1.3B.

If domestic P&R depreciation remains unchanged, then that comes out to $13B over the next 10 years. Given Iger’s previous $17B statement, growth capex for 10 years would be $4B.

However, depreciation nearly always increases over time. Disney domestic P&R depreciation has averaged a 6% annual increase for the last 10 years. If this pace continued, WDW 10-year depreciation might add to over $18B. Even if WDW depreciation increased by only 3%, Domestic P&R depreciation over the next 10 years would add to more $15B, leaving less than $2B in investment at WDW.

Best guess is that WDW growth capex will average $200M to $400M per year for the next decade.

But how does this compare to the past?

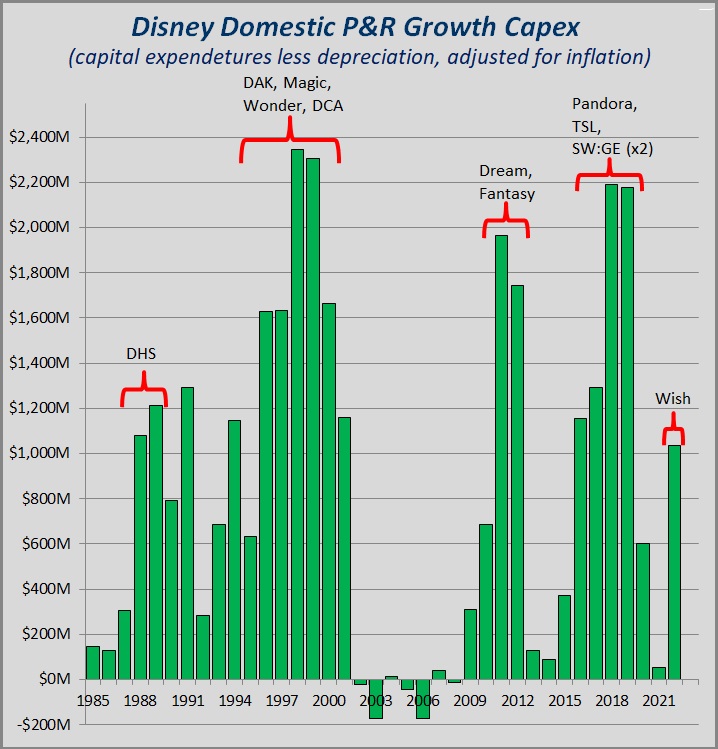

Luckily, I just happen to have a chart for this!

$200M to $400M per year is a good number. We should see a land or two (e.g. the Dinoland replacement and perhaps a new area behind Big Thunder Mountain), as well as a few attractions.

However, WDW growth won’t be at the same level as what we’ve seen more recently with Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, Toy Story Land, Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway, Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind, Ratatouille, Pandora, and TRON. As the chart suggests, Disney's larger investments since former Disney CEO Michael Eisner took over in 1984 far exceed the $400M threshold.

The problem is how much Disney spends to build. Take, for example, TRON. It’s a nice, fun rollercoaster. But rumor is that it cost $300M to construct. Universal’s VelociCoaster is more thrilling, and allegedly cost 1/3 that. Admittedly, Disney and Universal are targeting different audiences with these coasters, but it does suggest that $2B-to-$4B at WDW won’t go as far as it would elsewhere.

Disney’s financial failure known as Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser is being written off at a cost of $300M, and that’s a small (100-room) hotel with no windows or pools.

Again, Disney seems to spend money like no other park operator.

The Walt Disney Company is developing plans to accelerate and expand investment in its Parks, Experiences and Products segment to nearly double capital expenditures over the course of approximately 10 years to roughly $60 billion, including by investing in expanding and enhancing domestic and international parks and cruise line capacity.

Understandably, many want to know how much of this $60B will go to Walt Disney World (WDW).

During a shareholder's meeting on April 3, Disney CEO Bob Iger stated:

We’re currently planning now to invest over $17 billion in Walt Disney World over the next 10 years, and those investments, we estimate, will create 13,000 new Disney jobs and thousands of other indirect jobs, and they’ll also attract more people to the state and generate more taxes.

"Invest" is somewhat vague. Is this total capital expenditures or new investment?

Quoting from Investopedia:

Capital expenditures (CapEx) are funds used by a company to acquire, upgrade, and maintain physical assets such as property, plants, buildings, technology, or equipment. CapEx is often used to undertake new projects or investments by a company. Making capital expenditures on fixed assets can include repairing a roof (if the useful life of the roof is extended), purchasing a piece of equipment, or building a new factory. This type of financial outlay is made by companies to increase the scope of their operations or add some future economic benefit to the operation.

Company officers often use the terms "investment" and "capex" interchangeably. Disney’s more recent statements regarding the $60B specifically references capex. Presumably, the $17B mentioned by Iger is total capex.

So what does $17B of capex buy us at WDW?

Capex is the purchase of an asset that will benefit a company for several years. Capex can be lumped into two broad categories, investment (or growth) and maintenance.

Disney replacing an old bus with a new bus can be thought of as maintenance capex. Disney adding a new bus to increase the size of its fleet can be thought of as growth capex.

When Disney buys that bus, its purchase price does not impact profit immediately. Instead, the cost of the purchase is spread out over the number of years it will be used. This is called "depreciation". It's this depreciation that impacts profit.

Let's say that a Disney bus costs $500K and Disney intends to keep that bus for 10 years. That $500K does not reduce profit by $500K the year it is purchased. Instead, that bus affects profit for 10 years by $50K each year in the form of depreciation. (Disney uses the straight-line method to depreciate assets.) Once that bus exceeds its useful life, it should be replaced with a new bus. This is especially true at WDW where Guests expect (and pay for) high standards.

Without detailed disclosures, a rule-of-thumb is to estimate maintenance capex to be equal to depreciation. Amounts spent below depreciation are (or should be) for maintenance. Amounts spent above depreciation are for growth (or investment).

Since the $17B appears to include both maintenance and growth capex, we have to understand how much Disney spends on maintenance capex in order to calculate how much they have left for growth capex.

During the most recently completed fiscal year (2022), domestic P&R depreciation is $1.68B. Overwhelmingly, this consists of depreciation from WDW, Disneyland Resort (DLR), Disney Cruise Line (DCL), and Disney Vacation Club (DVC).

Historically, roughly 80% of domestic P&R depreciation was associated with WDW’s massive 25,000 acre facility. With three large cruise ships added, and another two on the way, that percentage is changing. Still, the change is not particularly great. For example, the Disney Wish went into service earlier this year. With a rumored cost of $1B and Disney’s straight line depreciation method taking this down to $150M (i.e. 15%) in 30 years (a standard approach to depreciate large vessels), the Disney Wish adds about $28M in depreciation per year. With total domestic P&R depreciation at $1.68B in 2022, that’s a 1.7% increase. Given recent additions to WDW also adding to depreciation, last year’s WDW depreciation probably is around $1.3B.

If domestic P&R depreciation remains unchanged, then that comes out to $13B over the next 10 years. Given Iger’s previous $17B statement, growth capex for 10 years would be $4B.

However, depreciation nearly always increases over time. Disney domestic P&R depreciation has averaged a 6% annual increase for the last 10 years. If this pace continued, WDW 10-year depreciation might add to over $18B. Even if WDW depreciation increased by only 3%, Domestic P&R depreciation over the next 10 years would add to more $15B, leaving less than $2B in investment at WDW.

Best guess is that WDW growth capex will average $200M to $400M per year for the next decade.

But how does this compare to the past?

Luckily, I just happen to have a chart for this!

$200M to $400M per year is a good number. We should see a land or two (e.g. the Dinoland replacement and perhaps a new area behind Big Thunder Mountain), as well as a few attractions.

However, WDW growth won’t be at the same level as what we’ve seen more recently with Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge, Toy Story Land, Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway, Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind, Ratatouille, Pandora, and TRON. As the chart suggests, Disney's larger investments since former Disney CEO Michael Eisner took over in 1984 far exceed the $400M threshold.

The problem is how much Disney spends to build. Take, for example, TRON. It’s a nice, fun rollercoaster. But rumor is that it cost $300M to construct. Universal’s VelociCoaster is more thrilling, and allegedly cost 1/3 that. Admittedly, Disney and Universal are targeting different audiences with these coasters, but it does suggest that $2B-to-$4B at WDW won’t go as far as it would elsewhere.

Disney’s financial failure known as Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser is being written off at a cost of $300M, and that’s a small (100-room) hotel with no windows or pools.

Again, Disney seems to spend money like no other park operator.