The [DIS] Influencer

Gary Snyder

How the Walt Disney Company Co-Opted the Voice of a Community

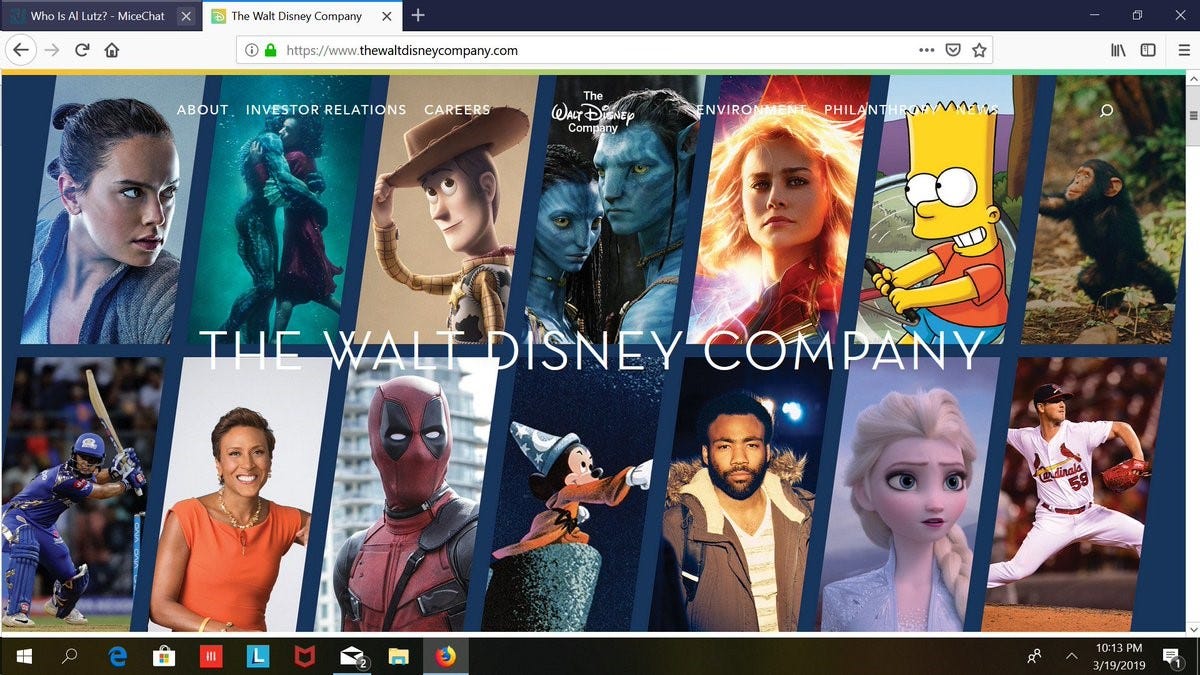

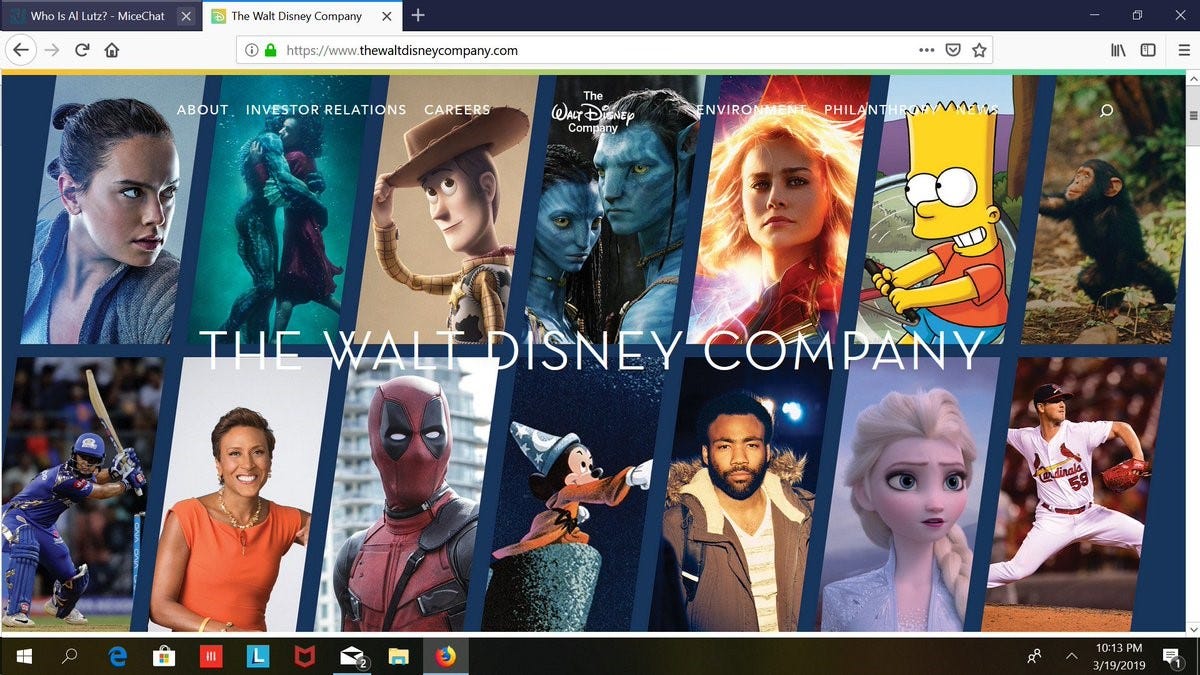

Screenshot of the Walt Disney Company’s

corporate homepage following the 21st Century Fox merger.

By Gary Snyder

Oh Mickey.

Just after midnight on March 20, 2019, rendered in perhaps his most famous role as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Mickey Mouse sat square in the middle of a new corporate landing page for the world to take in all that is now the Walt Disney Company. To his immediate left, the affable ambassador of not merely a corporate leviathan but of America itself was bordered by

Marvel’s Deadpool. To his right,

Lucasfilm’s Lando Calrissian. And just above the word “Disney,” over the ubiquitous mouse, was an image of

Avatar’s Jake Sully and Neytiri.

The jarring juxtaposition of images aside, each story behind those three pieces of intellectual property — now part of the Disney vault — runs counter to the core mission of the company’s eponymous founder. Far from family entertainment, they arc from a degenerate mercenary drawn from the world of Marvel Comics to a human trafficker in the Star Wars canon to the architects of genocide as James Cameron’s Avatar took corporatocracy to the extreme of the sci-fi realm.

But, beyond the

$244 billion media company that exists in its current form less as a product of creative ambition and more as the result of by-the-numbers acquisitions, there is the veneer of that name: Walt Disney. Still today, more than a half of a century after his death, it implies something. If it is Disney, it is quality. If it is Disney, it is family-friendly.

If it is Disney, it can be trusted.

Only, as the Walt Disney Company surveyed the cyber-scape of a

post-September 11th world in the early aughts, its corporate overlords began to realize the company was poorly positioned as traditional media in a then-new click-to-publish atmosphere where anyone with an Internet connection had the potential to turn a carefully crafted public relations campaign into the current-day equivalent of a meme. And, for the first time, Disney found itself on the receiving end of searing criticism from its most loyal fans while, at the same time, roiling from

the failed launch of a second theme park across from the original Disneyland.

Enter Al Lutz. An unremarkable, meek if passionate former recording industry executive who gained a following in the early days of online engagement with Usenet, Internet newsgroups where everyday folks could share and amplify their opinions without the glass ceilings and filters or credential-minded gatekeepers of major media’s domain.

Known for “The D-I-G,” or the

Disneyland Information Guide, Lutz began his online life as a resource for individuals who were planning a trip to Anaheim, California. Often, where Disney had failed to make up-to-date information on the park available online, he would deliver a just-as-it-is breakdown of everything from park hours to attraction closings to dining and lodging options.

He also would post sometimes

harsh criticism of the failings of Disney’s management with regard to the park and, while regularly mocked for mentioning matters as trivial to some as peeling paint and burned out light bulbs, Lutz had earned his bona fides among Disney’s most ardent fans of its theme parks and the company itself by being a reliable, and remarkably accurate, font of information.

This presented a problem for Team Disney Anaheim, where the feet-on-the-ground operations are based, and in the highest reaches of Burbank at the Walt Disney Company’s headquarters off Buena Vista Street. As Lutz had not only grabbed the cyber-tethers of the still nascent online fan community who would wait for an update from ‘their’ man in the field, he had increasingly become the turn-to critic mainstream journalists would go to for a quote on the company.

Complaining about chipped paint on the facade of a dressed-up carnival ride in Fantasyland was one thing, being

cited as an authority by the

Los Angeles Timeswas something entirely different.

As Disney’s California Adventure opened in February of 2001 to a less-than-enthusiastic response, Lutz became an entrenched voice of discontent. From behind the screen of his computer, he lashed out at executives like theme park chief Paul Pressler, the target of his online campaign “

Promote Paul Pressler!,” with energy anew over the perceived neglect of what had become, to him and his followers, their Disneyland.

Except now, it was the

Disneyland Resort. With a new resort hotel, a shopping and dining area, a massive parking structure and major infrastructure improvements in what had been named the Anaheim Resort District. And, aside from the significant expenditure by Disney, the reputation of the very company whose founder is credited as having invented the theme park found itself being held to account for what Burbank was having to admit was, in its best light, a missed opportunity with Disney’s California Adventure. More aptly framed, this was the failure of its long awaited expansion.

Among fans and Disney executives alike, there was no bigger name than Al Lutz. Soft as the exterior was, this almost first of his kind online personality hit hard. As Dave Gardetta wrote in

Los Angeles Magazine of Disney’s most well-known blogger, “He’s its Walter Winchell.”

Enter George Kalogridis. A career employee of the company whose backstory was part of the corporate selling of tens of thousands of low-wage, dead-end jobs for employees Disney terms “cast members.” Kalogridis started at the opening of

Walt Disney World in 1971, as a busboy at the Contemporary Resort, one of the resort hotels to open with the park.

Now, 30 years later, in late 2001, Kalogridis was second-in-command of the Disneyland Resort — a resort suddenly in trouble. Suddenly under tremendous scrutiny. But, the scrutiny was not coming from the local media or government, which had paid handsomely for the resort’s expansion. The scrutiny was coming from someone who may well have been the first influencer as these individuals would come to be known.

That was Al Lutz.

Although today the word

‘influencer’produces positive images of polished Instagram posts and well-produced digital clips that work as de facto marketing arms of major companies, the idea of employing the influence of an online voice grew as a reactionary step by companies to online as well as real world critics. Kalogridis wanted to know how to blunt that criticism.

I know because I was one of the individuals he consulted. A few years earlier, I had met George Kalogridis when he was the vice president of Disney’s second park in Orlando — the former EPCOT Center — and I was a guest of corporate for the Walt Disney World Millennium Celebration on December 31, 1999.

When he was promoted to the job in Anaheim, I was one of the first people he told. When the Disneyland Resort had its debut in February of 2001, I was his personal guest. My personal host was another Disney employee, Andrew Hardy, who would become George’s husband.

So then it made sense, knowing my depth of knowledge of the industry and familiarity both with him and the growing online presence of Lutz and others, that he would ask.

And ask he did. Driving down from Los Angeles on a pleasant afternoon in late 2001, I met George for lunch at a sparsely attended Disney’s California Adventure. There, the prim-to-pretentious executive selected a quick-service dining location called Taste Pilots’ Grill in a wide step outside of the normal fine dining we would enjoy. We ordered salads, served in plastic containers and eaten outside just under the monorail beam. With the park so unpopular and the economy struck by the attacks of 9/11, however, we had not a single guest sharing the outside dining area with us.

It was clear both George and the new Disneyland Resort were in trouble.

George saw an abrupt end to his career. Disney saw its reputation as the world leader in themed entertainment heading for a potentially unrecoverable fall.

This was unacceptable. Most especially to Zenia Mucha.

Mucha earned her reputation as an off-with-their-heads but always-on-message political operative for then-New York Governor George Pataki who came to Disney’s

ABC television network having been courted by Robert A. Iger. At the time, Mucha had turned her role as communications director and advisor to the governor to include, as the

New York Times noted, “virtually every major decision made by the governor.

”

Arriving on-scene

in Burbank, the rise was swift and deliberate. By May of 2002, with longtime CEO Michael D. Eisner in a curiously choreographed media swiftboating, Mucha, who was known as “Director of Revenge” in her prior life as a politico and termed “

Mickey Mouse’s Karl Rove” by journalist Matt Stoller, was promoted to director of corporate communications for ABC’s parent company — the Walt Disney Company. Replacing John Dreyer, a trusted and loyal keeper of the Disney brand, Mucha was a harsh turn from the almost family-like atmosphere Michael Eisner and Frank Wells, Disney’s former president, had fostered as part of their rise to the very top of the House of Mouse.

Indeed, Jody Dreyer, Eisner’s longtime personal assistant and herself a member of the corporate communications department, was married to John. Without delay, however, Mucha had arranged the chairs to position herself as the eyes and ears of the company’s most senior executives. As John Dreyer took time away to “pursue other opportunities,” it became apparent Mucha’s ‘eyes and ears’ (which is also the name of an intracompany publication) were not necessarily there for the benefit of the individual she, at least as her job description stated, reported to: Michael D. Eisner.

From within the company, there were continuing concerns its new communications director might well have been positioned in Eisner’s office to advance the interests, to fulfill the ambitions, of Robert Iger, then-president of Disney subsidiary ABC, who is widely cited as having been instrumental in her rapid rise once at Disney. After all, he brought her into the fold — and, it had long been rumored, held

major political ambitions. Of course, being the head of a network when that network is a subsidiary of the Walt Disney Company under a celebrity-esque CEO who fashioned himself as a reanimated “Uncle Walt” does not get you much in the way of press.

That was Mucha’s domain. Enter the “Save Disney” campaign.

(Photo courtesy of “

Disney CEO Fumbles Entry to China,” by Gary Snyder, for the Huffington Post.)

Within a year of moving into her office in the building held up by the Seven Dwarfs on the lot in Burbank, what had started as rumblings that Roy E. Disney and business partner Stanley Gold, who had drafted Eisner and Wells nearly 20 years prior, were becoming the eighth dwarf — Malcontent — became a full-bore mutiny. Suddenly dissatisfied with the direction of the company, Disney and Gold vocally called for the removal of Eisner. Labeling the Walt Disney Company under Eisner, and ironically given the company that now is, “a rapacious, soul-less conglomerate” void of a succession plan.

If an online campaign of any sort seems out of character for the nephew of the company’s founder, who was most known for the ouster of Ron Miller, Walt Disney’s son-in-law, as the head of Disney to allow for Eisner and Wells’ entry, that is likely because it could not have been more outside of his lane. After all, not only had Eisner built the company that was headed for a hostile takeover with accompanying break-up for parts and profit into a global media behemoth, in a move that led to what has been termed Disney’s second

Golden Age in animation, he appointed Roy chairman of the animation department.

Now, if an online campaign by an individual sharing the name Disney sounds more like the move of a savvy political operative, you might be inclined to look over at the individual recruited by Eisner’s successor as CEO. You might want to look at the person brought over from Governor Pataki’s office: Zenia Mucha.

Oh, and the timid if intense fellow who once introduced a classical music take on some of

Disney’s most beloved tunes. The former recording industry executive. Al Lutz.

Admittedly, it does seem like an odd pairing. And it is. Yet, on the homepage of

SaveDisney.com, prominently featured, was a link to what was represented as Lutz’s latest and greatest hits on Disney and its leadership under Eisner. True to the reputation of the online enigma that Lutz had grown into, it was unforgiving.

It also was not Al Lutz proselytizing to his followers who might be planning a visit to Disneyland or might have visited one of the Disney parks.

Mucha had identified, early on, the power of the World Wide Web and the potential to employ

a vast network of ‘volunteers’ to bring about a certain outcome. And, in what may well be the first example of online gaslighting and the launch of brand ambassadors or advocates — now termed influencers — Mucha’s department, and the corporate communications director for what is now the world’s largest media company and the home of a major news network, had set their sights on a proxy. That proxy? It was Al.

Except, the recording industry guy turned media company gadfly was hardly able to produce the content, the strategic strands of nouns and verbs, required. No problem. From behind a keyboard, as the world has learned, anyone can pretend to be anyone. So, it appears, she did.

Mucha’s Disney recruited a hungry-as-a-dog-before-dinner and needier-than-a-new-arrival-to-Sunset-Boulevard cast member. Even gave him an impressive title to use, Corporate Liaison for Imagineering & Operations (“CLIO”).

No, that would not be Al. That was Troy C. Porter.

Except, to everyone clicking on that link at

SaveDisney.com and everyone reading the columns produced, they thought they were reading the thoughts, observations and ramblings of their ‘old friend’ from The D-I-G. Instead, they read carefully crafted copy to

undermine the leadershipof Disney CEO Michael Eisner.

To this day, while Al Lutz has been in the later stages of Parkinson’s disease, the antagonistic voice of the fan community that is grating and caustic at the same time as it is homespun in that dysfunctional and abusive manner has been maintained as his. It is not.

By December of 2002, the online personality known as “Al Lutz” left the Disney fan site he co-founded,

MousePlanet, and started

MiceAge (later to be hosted by

MiceChat, whose placeholder was and remains a backseat-blazer wearing and Simonized-smile dressed character known as “Dusty Sage,” who is, in real life, an individual with dubious connections to the Walt Disney Company named Todd Regan).

Quickly redirecting Al’s followers, Porter was engaged and continuously employed to ferry the talking points that seemed to advance the position of Mucha and Iger while, at the same time, undermining the leadership of — and, more importantly, the faith of the financial community in — Eisner. All, apparently, using the faux voice of an early superfan as misappropriated by the very corporate communications office of the head of the entire company.

All using the company’s co-founder’s son as a dupe in the

Save Disney puppet show which was, in appearance if not fact, a corporate ops stratagem of Mucha and Iger.

The goal being, of course, to replace one “Uncle Walt” with another. Here, replacing Eisner with Iger in, what then was thought to be, an effort to position the latter on a launching board to high-level political office. The bailiwick of none other than Zenia Mucha.

And, for nearly a generation, it stayed positioned just so. The facade, as meticulously as they had crafted it, stood. Then, as typically happens, they got sloppy. Stupid. Arrogant. Or, maybe they were always that and folks simply did not think to question it — to pull pack the curtain to see what lurked behind it.

Dating to the mid-1990s, when Troy Porter relocated from Oregon to Southern California to work for Disney, he began posting on the Usenet boards. His

online moniker was TP2000. To this day, on fan sites, you can find this same poster under an assumed persona posting about the behind the scenes happenings at Disneyland and within the Walt Disney Company.

Presenting as an Orange County Log Cabin Republican with a penchant for spinning yarns about “the neighbor lady” and “things overheard about the goings-on at Disney,” he seemed near-pitch perfect to adopt the writing voice Mucha and the top tier of Disney’s corporate communications department thought would sell to this new if soon-to-be industry-of-its-own

medium of passionate fans who devoted significant portions of each day following every move of the company.

So Troy Porter became Al Lutz. Or, as the fans would see it, Al Lutz became somehow different yet familiar. But the con was in. Set. And it has stayed in position for all of these years with Disney listening in on and eventually manipulating

discussion boards into controlled focus groups lorded over like a corporate clubhouse hidden in the backroom of your local YMCA.

From a former partner of Regan’s and housemate of Al’s, “I cannot say that Al ever wrote a single column for

MiceAge or

MiceChat.” And, in fact, studying the writing voice and the spot-on information distilled in a manner at once disparaging and dispiriting and yet also weirdly complimentary, or strategically complimentary, the fingerprints are all there.

These works were cut-and-paste-and-forward writings that read as though precisely positioned by Disney’s Mucha & Co.

“It always seemed as though, while people thought Al had all of these sources, something he would do nothing to dissuade people from believing, he had only one — Troy Porter.”

Continuing on, another person familiar with the operations of the site that published ‘Al’s column,’ said, “When Al missed a week or two, it was because Troy hadn’t sent the copy to him.”

It appeared there was a not-so-small amount of narcissism at play among all involved, however. As, by early 2005, with the relentless attacks by ‘Al Lutz’ as promoted by

SaveDisney.com, the shareholders held a no-confidence vote and Eisner was on his way out. Who was to succeed him? Well, despite an alleged corporate search, there was only one candidate — Zenia Mucha’s.

Robert A. Iger.

The eventual undoing was vanity though. As Porter had become so accustomed to the feedback loop writing as Al presented, and posting on fan forums as TP2000, he continued writing. For years after the Save Disney campaign was little more than a

Wikipedia entry, Porter wrote as Lutz.

With the recent, and highest profile of Iger’s tenure, failure of the massive Star Wars land expansion,

Galaxy’s Edge, added cancer-like on the back of Walt’s hallowed Disneyland with a companion land coming to Walt Disney World in just a couple of weeks, Al has reappeared in a grand way. Make that, Troy Porter has reappeared.

The goal — the reason— could not be clearer. As Porter wrote

here, directing folks to ‘Al’s column’ on

MiceChat.com:

“I wonder does the current crop of Burbank execs and Bob Chapek even know how big a deal this is? Do they understand the weight that Lutz’s words have with the long-term West Coast fan community? If I were Mr. Chapek, I would be concerned that I did indeed cut things a bit too far and awakened the Tiki Gods and Al Lutz.”

So, it seems, the ‘once an operative always an operative’ Mucha reenlisted that crusty old influencer from days of yore. Now, the need was even more urgent, as

Iger needed someone to take the fall, hard and fast, for the flailing and single largest expansion at Disneyland and anchor intellectual property for both domestic resorts. That would be Mr. Chapek, the as-if-stylized-by-Mr. Clean chairman of Disney’s Parks & Resorts division.

And that career employee of the Walt Disney Company who started as a busboy at Walt Disney World’s Contemporary Resort? George Kalogridis? Well, George might well have been Mucha’s only real conduit to Troy Porter. Where is George?

George Kalogridis is the president of Walt Disney World. The largest private single-site employer in America — marketed as the world’s top vacation destination.

According to the story, he started clearing tables. Now, he sits at the head of the table.

As for how this all came to be, this campaign that likely is the start of what is understood now as that of

the influencerwho grew out of something pure and passionate — a fan, it all came to be one fall day at the flailing theme park across from Walt’s original in Anaheim. Over lunch at Taste Pilots’ Grill.

When an executive from Florida, whose job with the company if not career was on the line, asked a friend who was an early participant in the online world of engagement and knowledgeable in advancing a brand or thwarting one how to counter the later named superfan.

“Control the message by controlling the messenger,” I said. “Acquire the voice.”

“You do not counter someone like Al. You cannot counter Al. You can, if done smartly, own that voice as your own — as a conduit of the Walt Disney Company.”

Now, you can grab the fresh-squeezed lemonade, add in some just brewed iced tea, even toss in a bit of an adult libation and ask

‘the neighbor lady’ if she knows anything about how a political operative came to script everyday Mouseketeers, a weatherman came to lead the world’s largest media company and a busboy came to run the world’s largest resort destination.

After being named the new president of the Walt Disney World Resort in January of 2013, the local newspaper ran a puff piece by Jason Garcia entitled, “

George Kalogridis: From clearing tables to Disney World chief.” Garcia wrote, “Kalogridis’ star has soared since he took over as president of Disneyland, where attendance and spending have ballooned…”

Quoted just below that: Al Lutz. “I think he showed up at the right time.”

Reflecting on that meeting in late 2001, over a mediocre Cobb salad with a man of middling potential who was seeking a spot on the mainstage, I am not entirely sure who Lutz was referring to.

Author’s Note: The Walt Disney Company declined to comment on this column.