I see this comment going around quite a bit, but I don't really understand where it's coming from. She only broke her alliance's trust after they broke hers. Deshawn tried to go behind her back to get out Ricard. Shan was planning to stick with the core four until that happened.She also deserved to go due to breaking people's trust.

-

The new WDWMAGIC iOS app is here!

Stay up to date with the latest Disney news, photos, and discussions right from your iPhone. The app is free to download and gives you quick access to news articles, forums, photo galleries, park hours, weather and Lightning Lane pricing. Learn More -

Welcome to the WDWMAGIC.COM Forums!

Please take a look around, and feel free to sign up and join the community.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Survivor 41 Discussion Thread

- Thread starter PUSH

- Start date

dmw

Well-Known Member

- In the Parks

- No

The Power 5 and Black Alliance gone with one tribal. There are no real alliances at this point. The social game is a complete toss-up going forward.

It was very telling that in the revote, everyone voted for Shan. She was the bigger threat than Liana. It was a very good move by Ricard. That should have been Deshawn's move last week - he blew it. Deshawn just lost any chance at winning, unless it is between him Heather and Erika.

Danny and Xander... I think they may be playing the best strategic game. Both staying out of the crosshairs, but involved in the key votes. They need to step it up now to take command. One needs to lead the charge to vote off Ricard.

Can't wait to see the new twist next week!

It was very telling that in the revote, everyone voted for Shan. She was the bigger threat than Liana. It was a very good move by Ricard. That should have been Deshawn's move last week - he blew it. Deshawn just lost any chance at winning, unless it is between him Heather and Erika.

Danny and Xander... I think they may be playing the best strategic game. Both staying out of the crosshairs, but involved in the key votes. They need to step it up now to take command. One needs to lead the charge to vote off Ricard.

Can't wait to see the new twist next week!

Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

I see this comment going around quite a bit, but I don't really understand where it's coming from. She only broke her alliance's trust after they broke hers. Deshawn tried to go behind her back to get out Ricard. Shan was planning to stick with the core four until that happened.

True enough.

Everyone was trying to make moves, and many people arguably made strategic errors.

Some people underestimated the Liana/Shan relationship and didn't realize the plan to oust Ricard would get to Shan.

Shan might have been better off not telling Ricard about the plan. It led to him confronting Deshawn and blew up her game.

Shan had the worst performance this week, obviously, but it could have gone so many different ways.

Erika had a good week. For someone who seemingly had no power she still convinced people to do a split vote that protected her.

I think the thing that ultimately led to Ricard going after Shan was his immunity win. When you have immunity is a great time to try and shake things up, because if it backfires, you're still safe. I remember Tyson and Andrea talking about making moves when they won immunity.True enough.

Everyone was trying to make moves, and many people arguably made strategic errors.

Some people underestimated the Liana/Shan relationship and didn't realize the plan to oust Ricard would get to Shan.

Shan might have been better off not telling Ricard about the plan. It led to him confronting Deshawn and blew up her game.

Shan had the worst performance this week, obviously, but it could have gone so many different ways.

Erika had a good week. For someone who seemingly had no power she still convinced people to do a split vote that protected her.

It was the perfect storm for Ricard. It's not that often where everything lines up like that.

No Name

Well-Known Member

I never loved Shan in the game and hated her Twitter hypocrisy, so I was glad to see everyone finally act with some agency and get rid of her. The irony is that the other 6 were able to keep a complete secret from the two people who set the whole thing in motion by not being able to keep a secret. Great episode.

So I'll preface this by saying I know not everyone is going to love this episode of Survivor, and there will be a lot of people saying exactly what Liana described: that Survivor shouldn't be a place for these conversations and that's not why people watch. I, for one, thought this episode was so incredibly interesting. These are things that black players have to take into account that I wouldn't even have to think about. And it's clearly not just a case of one person. It's clearly a part of the game, and it has been since season 1. They are just choosing to air more of it now, and it gives a clearer picture of what's actually happening and how the decisions are being made. It's all part of the social gameplay that Survivor is built around, and Liana did a masterful job of describing it. I am grateful that I got to see this episode and further learn and understand the challenges that black people face on Survivor and in the real world. How they're called racist or hypocrites because they're trying to portray the culture properly and be an inspiration for people who look like them.

I also think it's important how Xander spoke about his role and position in this conversation, and about his privilege. It's not an insult to be privileged, but it is important for someone like Xander (and myself) to recognize that there are privileges that do exist, and that impacts (or better worded... doesn't impact) different aspects of lives or the game of Survivor itself.

Moving on to the opening bits of the show. Ricard so eloquently and calmly explained how I've been trying to explain my thoughts on Deshawn. Deshawn is always finding someone else to blame, and mostly he blamed Shan. He blamed her for the communication mishaps, for backstabbing him after he came after Ricard first, and now for him being perceived as a snake. All of those things were partly, or entirely, his fault. He hasn't owned his game, not even during confessionals. Ricard was right... he's all over the place. He made a bad move for his game in voting out Shan, and I think he's realizing that and putting the blame on her. In hindsight, Deshawn should have voted out Erika last week. That would have kept the black alliance together and in power. Then he could have tried to scoop up Xander or Heather (or Ricard now that he's gone after Shan) later down the road to make it to the final three.

Danny had a really interesting episode. The story with his dad's passing was so captivating, and it was capped off by winning immunity. Very cool. During the challenge, both he and Ricard were switching hand grips throughout. I immediately thought of a Peridiam challenge hacks video on YouTube where he showed how Amanda won this challenge by switching her hand grip when they added new pieces.

I'm not a fan of the Do or Die twist. Production keeps minimizing the importance of the players voting, and it's taking away from the core of the game: to vote someone out. They need to trust in their casting process and trust that the players will make a good season. And their casting is better now than it has ever been. These savvy and interesting players will make a good show.

I also don't like how the players didn't know that it was only a 33% chance of survival. I assumed it was 50/50, but Deshawn had to be crushed when he saw it was a 1/3 shot of staying. And the process of how they were revealed was taken directly from Deal or No Deal. Jeff must have binge watched it during quarantine. You can't convince me otherwise.

Overall another really good episode. These past couple weeks have been so fascinating, and it takes me back to old school Survivor, despite the new twists and turns. The core of the episodes have been about the people and the social politics that the show was founded on back in Borneo.

And just a humble brag that I made Stephen Fishbach laugh tonight. He tweeted about Erika saying she was going to "roll the dice", and he said he thought the way dice worked was that you stuck them in an urn and drew out a parchment. I replied to him and said that's going to be the new phrase after this season: "I'm going to stick the dice in the urn and drew parchment." "Rolling the dice" will be obsolete. He tweeted back "alol" which stands for "actually laughing out loud". I just had to point that out.

Also... looks like the Shot in the Dark didn't have a huge impact. It could have if Sydney hadn't used it, but overall more of something they had to strategize around than actually had to deal with.

Moving onto my potential winner rankings. I'm just going to list them in my order... my headings change every week because they are so fluid anyway.

I also think it's important how Xander spoke about his role and position in this conversation, and about his privilege. It's not an insult to be privileged, but it is important for someone like Xander (and myself) to recognize that there are privileges that do exist, and that impacts (or better worded... doesn't impact) different aspects of lives or the game of Survivor itself.

Moving on to the opening bits of the show. Ricard so eloquently and calmly explained how I've been trying to explain my thoughts on Deshawn. Deshawn is always finding someone else to blame, and mostly he blamed Shan. He blamed her for the communication mishaps, for backstabbing him after he came after Ricard first, and now for him being perceived as a snake. All of those things were partly, or entirely, his fault. He hasn't owned his game, not even during confessionals. Ricard was right... he's all over the place. He made a bad move for his game in voting out Shan, and I think he's realizing that and putting the blame on her. In hindsight, Deshawn should have voted out Erika last week. That would have kept the black alliance together and in power. Then he could have tried to scoop up Xander or Heather (or Ricard now that he's gone after Shan) later down the road to make it to the final three.

Danny had a really interesting episode. The story with his dad's passing was so captivating, and it was capped off by winning immunity. Very cool. During the challenge, both he and Ricard were switching hand grips throughout. I immediately thought of a Peridiam challenge hacks video on YouTube where he showed how Amanda won this challenge by switching her hand grip when they added new pieces.

I'm not a fan of the Do or Die twist. Production keeps minimizing the importance of the players voting, and it's taking away from the core of the game: to vote someone out. They need to trust in their casting process and trust that the players will make a good season. And their casting is better now than it has ever been. These savvy and interesting players will make a good show.

I also don't like how the players didn't know that it was only a 33% chance of survival. I assumed it was 50/50, but Deshawn had to be crushed when he saw it was a 1/3 shot of staying. And the process of how they were revealed was taken directly from Deal or No Deal. Jeff must have binge watched it during quarantine. You can't convince me otherwise.

Overall another really good episode. These past couple weeks have been so fascinating, and it takes me back to old school Survivor, despite the new twists and turns. The core of the episodes have been about the people and the social politics that the show was founded on back in Borneo.

And just a humble brag that I made Stephen Fishbach laugh tonight. He tweeted about Erika saying she was going to "roll the dice", and he said he thought the way dice worked was that you stuck them in an urn and drew out a parchment. I replied to him and said that's going to be the new phrase after this season: "I'm going to stick the dice in the urn and drew parchment." "Rolling the dice" will be obsolete. He tweeted back "alol" which stands for "actually laughing out loud". I just had to point that out.

Also... looks like the Shot in the Dark didn't have a huge impact. It could have if Sydney hadn't used it, but overall more of something they had to strategize around than actually had to deal with.

Moving onto my potential winner rankings. I'm just going to list them in my order... my headings change every week because they are so fluid anyway.

- Ricard - He's the obvious frontrunner for obvious reasons. As Xander said, he's the only one remaining who's made a successful move, and it was the biggest move you can make in the season. I think he's the only person left that could get all of the jury votes and sweep the other two he's sitting with.

- Deshawn - While I have my issues with how he's playing, I wouldn't be surprised if he wins. He led a pretty strong alliance, and he was a factor in deciding when it split up, even if he was more of a follower than the leader in that move. I think he has enough social capital to get votes at the end. And now he's on the bottom and will be forced to make some moves to get to the end, which would boost his resume.

- Xander - He has the ability to say he's been on the bottom the whole season, and he hasn't had to use his idol. There are some cases to be made that he was part of some moves, but overall I think he would have to rely on the underdog story. If he can get to the end, that will be powerful enough to get some votes.

- Danny - I struggled with Danny and Deshawn for this one. I opted with Danny to be above of her this week because I do think he has made some good social connections. Strategically, he at least can play the loyalty and consistency card. I don't think he will win, but it wouldn't be the most surprising thing to happen.

- Erika - While she's had some decent episodes lately, she still hasn't been in the driver's seat for any vote. And while nobody has except Ricard, she hasn't had much agency in the game. Her only hope would be to get votes as an underdog with a "rising star" story over the last few votes. She would need to sit next to Heather and Danny in order to have a chance.

- Heather - Again, there's not much to say here. All you need to look at are the jury's eye rolls as she speaks at Tribal Council. A win for Heather would literally be the most surprising thing to happen in Survivor history.

Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

I agree this was a good episode.

A lot of viewers, myself included, felt a little uneasy with alliances based on race because it feels like it goes against what we want diversity to be or because we worry it will be an ongoing strategy that ends up feeling divisive.

I'm glad they took the time to explain why that alliance formed, what it means, and what it doesn't mean.

At first I thought Danny was going home because he got a lot of backstory all of a sudden.

Then I thought Deshawn was going home because they didn't show any strategy talk at tribal council.

So, the show did a good job keeping me on my toes and being suspenseful.

The show going from prisoner's dilemma scenarios to Let's Make a Deal is low key hilarious.

As far as twists go, it's better than many have been. I liked the choice the players had to make in terms of sitting out or not. It added a new wrinkle to that choice, and was more interesting than food as a temptation.

However, a 50/50 chance of not going to a vote goes against the core of Survivor.

I think this twist has potential if they tweak it. Maybe the risk is, if you drop out first you can't play any of your advantages that night. That puts pressure on anyone with an idol. Compete, but be at risk of going home with an idol. Sit out, but it means your only option for immunity is to play the idol.

A lot of viewers, myself included, felt a little uneasy with alliances based on race because it feels like it goes against what we want diversity to be or because we worry it will be an ongoing strategy that ends up feeling divisive.

I'm glad they took the time to explain why that alliance formed, what it means, and what it doesn't mean.

At first I thought Danny was going home because he got a lot of backstory all of a sudden.

Then I thought Deshawn was going home because they didn't show any strategy talk at tribal council.

So, the show did a good job keeping me on my toes and being suspenseful.

The show going from prisoner's dilemma scenarios to Let's Make a Deal is low key hilarious.

As far as twists go, it's better than many have been. I liked the choice the players had to make in terms of sitting out or not. It added a new wrinkle to that choice, and was more interesting than food as a temptation.

However, a 50/50 chance of not going to a vote goes against the core of Survivor.

I think this twist has potential if they tweak it. Maybe the risk is, if you drop out first you can't play any of your advantages that night. That puts pressure on anyone with an idol. Compete, but be at risk of going home with an idol. Sit out, but it means your only option for immunity is to play the idol.

Last edited:

Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

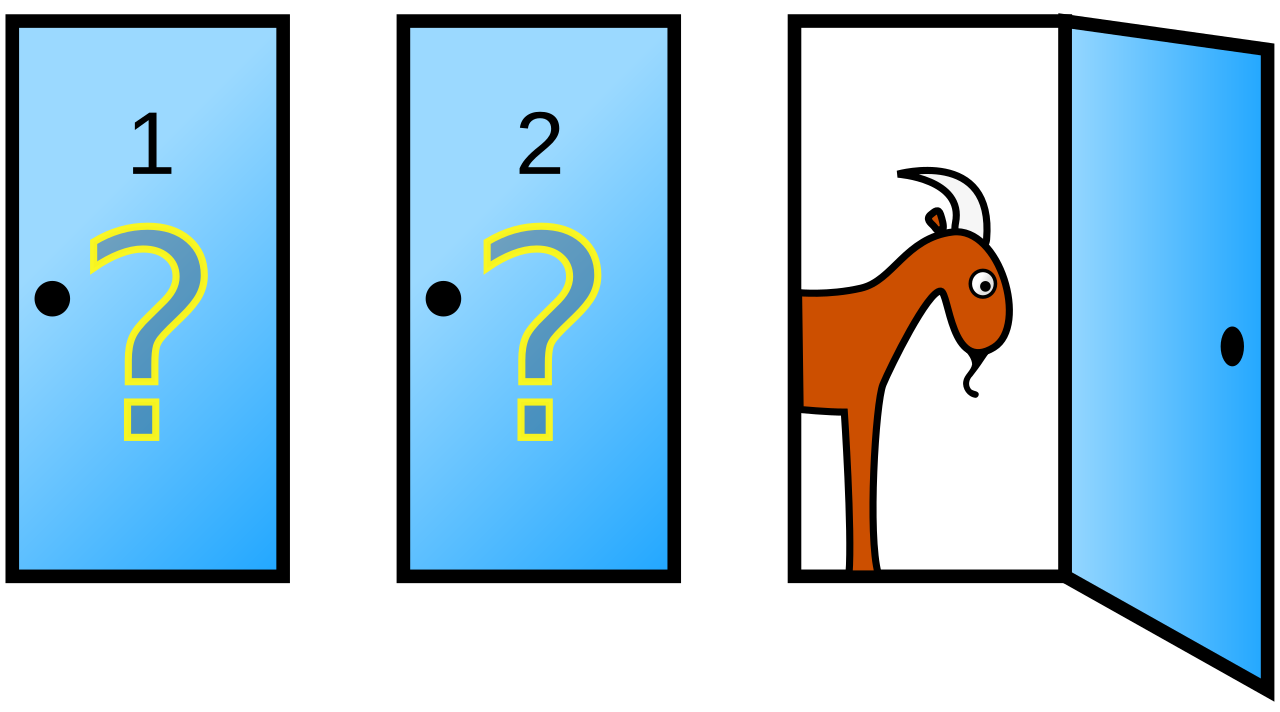

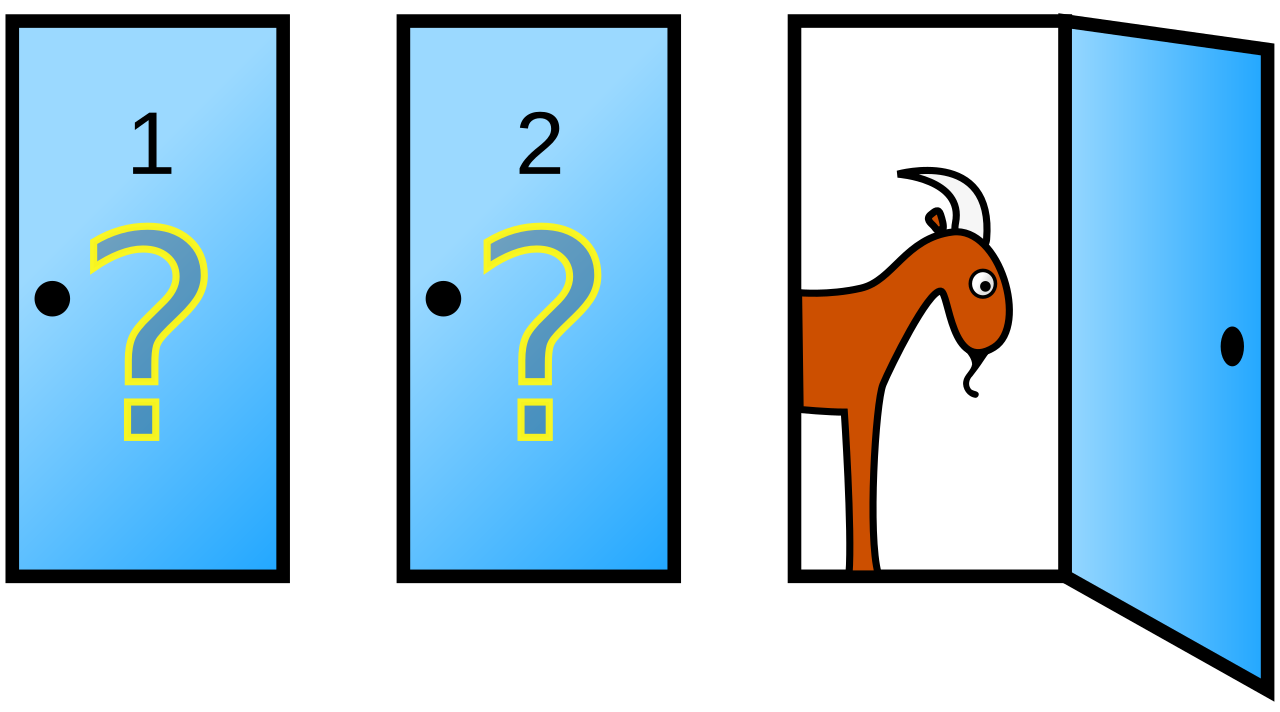

Apparently Deshawn made the wrong statistical choice with the boxes. The odds were against him. It's one of those things that is hard to wrap one's mind around.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Monty Hall problem - Wikipedia

The Monty Hall problem is a brain teaser, in the form of a probability puzzle, loosely based on the American television game show Let's Make a Deal and named after its original host, Monty Hall. The problem was originally posed (and solved) in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975.[1][2] It became famous as a question from reader Craig F. Whitaker's letter quoted in Marilyn vos Savant's "Ask Marilyn" column in Parade magazine in 1990:[3]

Vos Savant's response was that the contestant should switch to the other door.[3] Under the standard assumptions, the switching strategy has a 2/3 probability of winning the car, while the strategy that remains with the initial choice has only a 1/3 probability.Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

When the player first makes their choice, there is a 2/3 chance that the car is behind one of the doors not chosen. This probability does not change after the host opens one of the unchosen doors. When the host provides information about the 2 unchosen doors (revealing that one of them does not have the car behind it), the 2/3 chance of the car being behind one of the unchosen doors rests on the unchosen and unrevealed door, as opposed to the 1/3 chance of the car being behind the door the contestant chose initially.

The given probabilities depend on specific assumptions about how the host and contestant choose their doors. A key insight is that, under these standard conditions, there is more information about doors 2 and 3 than was available at the beginning of the game when door 1 was chosen by the player: the host's deliberate action adds value to the door he did not choose to eliminate, but not to the one chosen by the contestant originally. Another insight is that switching doors is a different action from choosing between the two remaining doors at random, as the first action uses the previous information and the latter does not. Other possible behaviors of the host than the one described can reveal different additional information, or none at all, and yield different probabilities.

Many readers of vos Savant's column refused to believe switching is beneficial and rejected her explanation. After the problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine, most of them calling vos Savant wrong.[4] Even when given explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still did not accept that switching is the best strategy.[5] Paul Erdős, one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, remained unconvinced until he was shown a computer simulation demonstrating vos Savant's predicted result.[6]

The problem is a paradox of the veridical type, because Vos Savant's solution is so counterintuitive it can seem absurd, but is nevertheless demonstrably true. The Monty Hall problem is mathematically closely related to the earlier Three Prisoners problem and to the much older Bertrand's box paradox.

Tonight's episode was average. It's hard to top the past two, and I'm happy they didn't try to present us with a false option to save themselves from an obvious boot. They've done that pretty frequently in recent seasons, and it feels like we're being lied to.

Deshawn's game is very interesting. He seems to be a strategic leader at times, but it's impossible to point to one thing that is really a savvy decision. He seems like he's trying to make something stick, but nothing does. He hasn't really shown that he's a good player, but everyone seems to hold him in higher regard than most. The past few episodes it's seemed he's backed himself into the corner he's in. He's cut off all of his relationships and options to get to the end, and it all started with voting out Shan. That was a massive mistake for him. And now he may have blown his chance with Erika. He isn't able to read when people are with him, and it seems he's not willing to accept the relationships into his game. Outside of Danny, who has Deshawn really welcomed into his alliance? Nobody, really. He hasn't wanted Shan, Liana, Erika, Heather, Xander, Ricard, or anyone unless it's been the right time for him. It feels like he doesn't maintain relationships and only tries when he needs them, then questions why they didn't stick with him.

Erika's decision was interesting. It makes sense from her perspective to keep Deshawn, since it's one more option to get to the end.

And... who in their right mind it choosing cake, cookies, and candy over chicken and veggies?

My updated winner rankings:

1. Ricard

Deshawn's game is very interesting. He seems to be a strategic leader at times, but it's impossible to point to one thing that is really a savvy decision. He seems like he's trying to make something stick, but nothing does. He hasn't really shown that he's a good player, but everyone seems to hold him in higher regard than most. The past few episodes it's seemed he's backed himself into the corner he's in. He's cut off all of his relationships and options to get to the end, and it all started with voting out Shan. That was a massive mistake for him. And now he may have blown his chance with Erika. He isn't able to read when people are with him, and it seems he's not willing to accept the relationships into his game. Outside of Danny, who has Deshawn really welcomed into his alliance? Nobody, really. He hasn't wanted Shan, Liana, Erika, Heather, Xander, Ricard, or anyone unless it's been the right time for him. It feels like he doesn't maintain relationships and only tries when he needs them, then questions why they didn't stick with him.

Erika's decision was interesting. It makes sense from her perspective to keep Deshawn, since it's one more option to get to the end.

And... who in their right mind it choosing cake, cookies, and candy over chicken and veggies?

My updated winner rankings:

1. Ricard

If he's able to get to the final Tribal Council, he's the obvious winner. He's getting the Ben/Devens treatment of everyone in the game praising him, which only helps solidify his case in the end. And just like last week, he's the only player who has any kind of move on his resume. And he's dominating challenges. Plus, he can think of all the four letter words in a short amount of time. Pretty impressive.

2. DeshawnI'm personally not high on Deshawn's game, but it feels like he's the most likely challenger to Ricard. However, at this point if Ricard goes home, I don't think he will have the possibility to claim it as his move since everybody will likely be on board to vote him out. Nobody will be able to claim sole possession of the move unless something crazy happens.

3. XanderXander wouldn't surprise me as a winner, but he really hasn't done anything to earn it. He would benefit from the rest of the finalists not having much on their resumes, either. It feels like as a whole, nobody really has solid relationships, either. Perhaps that's an outcome of a shortened season with less time and less down time to develop personal connections. But I think that benefits Xander and puts him on an even playing field.

4. ErikaAt this point, an Erika win wouldn't shock me, but I would be questioning it. She hasn't done a whole lot, but we've seen her strategic point of view throughout the whole season, even if it's been brief at times. We've seen winners like her before in Michele and Natalie White. Under the radar winners who may have been under edited due to bigger personalities around them.

5. HeatherThere is absolutely no way Heather is winning. Also, Jeff was a savage at the immunity challenge, "That's okay, Heather, you've struggled before!"

Looking forward to the finale! It's been a good season, but it'll be challenging to rank. If not for the first half of the season being dedicated to reading parchment and learning failed twists and advantages, it would probably rank pretty high. But those reasons bring the ranking down. At this point, I would probably have it ranked in the 15-20 range before the finale. I would have to look at my actual rankings, though. That's just off the top of my head.Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

Why wasn't Xander (and his idol) brought up as a target? Was it because the four just didn't want to risk Deshawn or Danny making it through the final five vote?

That's the trouble with the fire making and having a final three. Makes things a bit predictable at this point, much of the time. You'd think some players would try and end tonight with a 3-2 advantage.

That's the trouble with the fire making and having a final three. Makes things a bit predictable at this point, much of the time. You'd think some players would try and end tonight with a 3-2 advantage.

dmw

Well-Known Member

- In the Parks

- No

I think the game is Ricard's to lose at this point. If he keeps winning immunity and makes the final 3, he wins. If he does not win immunity, he will be voted out. Deshawn blew it by not voting Ricard off before now.

Xander is my pick as next most likely. He survived at the bottom playing the social game, and I don't think he has any enemies in the jury. He's probably the target vote next week if Ricard gets immunity. Thus, Xander would need to play his idol at the next tribal. And I love how he was just so honest about why he voted the way he did. He is definitely playing a smart game.

Deshawn has not shown enough boldness in moves, relationships, etc. He has missed opportunities for key moves. I would pick Erika to win over Deshawn if they both make it to Final 3. Heather will make the final three, because she is no threat to win.

Xander is my pick as next most likely. He survived at the bottom playing the social game, and I don't think he has any enemies in the jury. He's probably the target vote next week if Ricard gets immunity. Thus, Xander would need to play his idol at the next tribal. And I love how he was just so honest about why he voted the way he did. He is definitely playing a smart game.

Deshawn has not shown enough boldness in moves, relationships, etc. He has missed opportunities for key moves. I would pick Erika to win over Deshawn if they both make it to Final 3. Heather will make the final three, because she is no threat to win.

Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

Probably don't need a poll given the low number of people posting here.

Heather appears to have zero chance. Xander appears to be a non-factor given how the other players have no qualms letting him coast to the final four with an idol in hand.

I'd be shocked if it's not one of the other three.

Ricard played a great game, but failed to manage his threat level. The fact that everyone is gunning for him is not good. He still has a chance of getting through and would be the odds on favourite if he's in the final three.

Deshawn has put himself in a better position. His alliance overplayed their hand when they basically announced they were a foursome, but they were effective otherwise. He's also the sole remaining member which gives him an underdog story and friends on the jury. He's done well but has played a bit more under the radar so all eyes are on Ricard.

Erika could come from behind to win. Like Deshawn she hasn't put a target on her back and has made the moves she needed to when she needed to.

My best guess at this point would be Deshawn.

Heather appears to have zero chance. Xander appears to be a non-factor given how the other players have no qualms letting him coast to the final four with an idol in hand.

I'd be shocked if it's not one of the other three.

Ricard played a great game, but failed to manage his threat level. The fact that everyone is gunning for him is not good. He still has a chance of getting through and would be the odds on favourite if he's in the final three.

Deshawn has put himself in a better position. His alliance overplayed their hand when they basically announced they were a foursome, but they were effective otherwise. He's also the sole remaining member which gives him an underdog story and friends on the jury. He's done well but has played a bit more under the radar so all eyes are on Ricard.

Erika could come from behind to win. Like Deshawn she hasn't put a target on her back and has made the moves she needed to when she needed to.

My best guess at this point would be Deshawn.

Listening to exit interviews, I get the sense that the jury doesn't think too highly of Xander. Danny says they let him get this far with his idol because nobody really considers him a threat in the end. That's one person, but still. Tiffany also seemed to be irked by Xander.

I'm thinking it's Ricard. I think he's either going at 5, or he's winning. I don't think they would edit him to be this masterful player, then have him lose in final four fire making. He also seems like someone who could make fire, and he's also an immunity threat at 4 given they like to run concentration challenges at that point. He seems like the player who can focus in the best.

After Xander, I think Deshawn is the next most likely candidate. Then Erika. Erika is perceived as a strategic player by at least some on the jury, and she has the underdog story.

Xander would be next, and I think the only way he can win is if he beats Ricard at fire.

Heather is a nice person.

I'm thinking it's Ricard. I think he's either going at 5, or he's winning. I don't think they would edit him to be this masterful player, then have him lose in final four fire making. He also seems like someone who could make fire, and he's also an immunity threat at 4 given they like to run concentration challenges at that point. He seems like the player who can focus in the best.

After Xander, I think Deshawn is the next most likely candidate. Then Erika. Erika is perceived as a strategic player by at least some on the jury, and she has the underdog story.

Xander would be next, and I think the only way he can win is if he beats Ricard at fire.

Heather is a nice person.

I'll post more in depth thoughts tomorrow, but just a baseline reaction...

Erika is going to be viewed as an undeserving winner by some, but I think she played a really solid game. I am a little disappointed how under edited she was, but I do think the editors shifted their strategy to put everyone on an even playing field in the end.

I was reading how they edited past seasons when trying to predict the winner, which is why I thought Deshawn had a good shot. But my gut feeling about how he was playing the game was more accurate.

I'll update my season, winner, and player rankings tomorrow, but my initial feeling is that 41 is a top half season, probably landing somewhere between 15-20. It would be higher, but it once again relied to much in twists, especially in the premerge. The postmerge was really good up until the finale, which was pretty predictable. But many finale are predictable. There's only so many ways to break things down when you get so few people, and at some point the editors have to wrap up the story.

I would say Erika is a middle of the pack winner. Maybe somewhere around 20, but I'll have to look at exactly who I have in which spots.

For players, I definitely think Ricard was the best player of the season. I don't think that's a debate. He's an all around great player strategically, socially, and physically. He's the total package. I would say Shan is the second best, but there's a solid gap between her and Ricard. After that I would probably say Erika, but I'll have to take a closer look.

Overall it was a satisfying ending. I like Erika as a winner. She knew her mission and executed it perfectly. I'm happy we have our first female winner in 7 seasons, even if we could have seen more of her. She seemed to have a good read on everything that was happening in the game at all times, which not many players can say.

Erika is going to be viewed as an undeserving winner by some, but I think she played a really solid game. I am a little disappointed how under edited she was, but I do think the editors shifted their strategy to put everyone on an even playing field in the end.

I was reading how they edited past seasons when trying to predict the winner, which is why I thought Deshawn had a good shot. But my gut feeling about how he was playing the game was more accurate.

I'll update my season, winner, and player rankings tomorrow, but my initial feeling is that 41 is a top half season, probably landing somewhere between 15-20. It would be higher, but it once again relied to much in twists, especially in the premerge. The postmerge was really good up until the finale, which was pretty predictable. But many finale are predictable. There's only so many ways to break things down when you get so few people, and at some point the editors have to wrap up the story.

I would say Erika is a middle of the pack winner. Maybe somewhere around 20, but I'll have to look at exactly who I have in which spots.

For players, I definitely think Ricard was the best player of the season. I don't think that's a debate. He's an all around great player strategically, socially, and physically. He's the total package. I would say Shan is the second best, but there's a solid gap between her and Ricard. After that I would probably say Erika, but I'll have to take a closer look.

Overall it was a satisfying ending. I like Erika as a winner. She knew her mission and executed it perfectly. I'm happy we have our first female winner in 7 seasons, even if we could have seen more of her. She seemed to have a good read on everything that was happening in the game at all times, which not many players can say.

Wendy Pleakley

Well-Known Member

I didn't like the advantage. It wasn't a minor advantage and really seemed to decide the immunity win. That win came down to who found a clue in a random bunch of trees first.

Fire making is bad for many reasons, and I'll quote Mike Bloom below on why a final four vote can be so much more interesting. Regardless of that, why is it not harder to burn the rope? Neither of them built a solid or good fire. Yeah, it was close and was exciting but I didn't feel it was a battle of skills.

I really liked the final tribal council. The questions and answers were all good and everyone was included. The interjections from the jury were useful and appropriate.

Very happy with the final result. Erika deserved it. She played well but not too well, which is the fine line needed to win Survivor and one of the reasons it's such an entertaining show.

I disagree with Ricard being the best player of the season. Looking back in hindsight Ricard did a lot of great things but failed spectacularly when it came down to managing his threat level. He should have kept Shan. The moment she left he had a bullseye painted on him. Xander played it perfectly by keeping a shield and getting rid of him at the right time.

Fire making is bad for many reasons, and I'll quote Mike Bloom below on why a final four vote can be so much more interesting. Regardless of that, why is it not harder to burn the rope? Neither of them built a solid or good fire. Yeah, it was close and was exciting but I didn't feel it was a battle of skills.

I really liked the final tribal council. The questions and answers were all good and everyone was included. The interjections from the jury were useful and appropriate.

Very happy with the final result. Erika deserved it. She played well but not too well, which is the fine line needed to win Survivor and one of the reasons it's such an entertaining show.

I disagree with Ricard being the best player of the season. Looking back in hindsight Ricard did a lot of great things but failed spectacularly when it came down to managing his threat level. He should have kept Shan. The moment she left he had a bullseye painted on him. Xander played it perfectly by keeping a shield and getting rid of him at the right time.

dmw

Well-Known Member

- In the Parks

- No

well... the only part of my prediction I got correct was that Ricard would be out in the final vote if he did not win immunity. Erika winning at the end was a big surprise to me, but she did play a good game. I really thought Xander was the next best player after Ricard, especially using Ricard as a shield. He executed that strategy perfectly. He may have been the next best player but as Ricard noted, Survivor history is full of best players who did not win. It's all about the jury.

No Name

Well-Known Member

I was really hoping Ricard would win. Drop the 4, keep the 1. Drop the h, keep the Ricard. I felt like the final four and final tribal wound up being a battle between fairly lame players which was unfortunate.

Season 42 is feels incredibly unoriginal… it’s structurally identical to 41, and will really have to be driven by great characters for it to shine. Haven’t been so apprehensive toward an upcoming season.

Season 42 is feels incredibly unoriginal… it’s structurally identical to 41, and will really have to be driven by great characters for it to shine. Haven’t been so apprehensive toward an upcoming season.

I think the problem with Ricard managing his threat level was that really nobody other than Shan had done anything, but he couldn't wait to get Shan out because after that final 8 vote, Shan and the black alliance have control of the game. And at the final 7, it would start to make sense for Shan to vote out Ricard. So I don't think Ricard could have waited. I think he had to make that move to have any shot of making it to the final three, and that's not his fault.

Most of the time, the best player doesn't win the season. It all depends on what criteria you have for "the best".

I've also heard a lot of people say that Xander was a great player, and he was robbed (to put it lightly). If you pay attention to the exit press, nobody was concerned about Xander. They viewed him as a non-entity. He didn't have connections, and he really was just there for the ride. He was the goat of the season, not Heather. Ricard said in his exit interview with Dalton Ross that Heather was seen as a bigger threat than him. He had really bad reads of people and their perceptions. They weren't sure about his logic of taking Erika so she didn't have a chance at making a big move by winning fire, when literally everyone knew she couldn't make fire. The jury knew she couldn't, and she told everyone it took her several hours to make fire on Exile. So they weren't sure why he brought the biggest threat when everyone else was telling Xander that Erika is the biggest threat, and they've been telling him for a while. He also couldn't think of a single social strategy in the final Tribal Council. But all in all, the other players had known for a while that he was a goat, and there were several plans to take him to the final 3 because he was easily beat. This is also not taken from one exit interview. It is taken from many throughout the season.

I just wanted to put that info out there, since it's a stark contrast from what we were shown in the edit. He was not portrayed accurately, which is a little irritating as a fan. Rob and Stephen were speculating that they need a new Ozzy/Malcolm type, so they made him be the fan favorite and the person kids love.

Most of the time, the best player doesn't win the season. It all depends on what criteria you have for "the best".

I've also heard a lot of people say that Xander was a great player, and he was robbed (to put it lightly). If you pay attention to the exit press, nobody was concerned about Xander. They viewed him as a non-entity. He didn't have connections, and he really was just there for the ride. He was the goat of the season, not Heather. Ricard said in his exit interview with Dalton Ross that Heather was seen as a bigger threat than him. He had really bad reads of people and their perceptions. They weren't sure about his logic of taking Erika so she didn't have a chance at making a big move by winning fire, when literally everyone knew she couldn't make fire. The jury knew she couldn't, and she told everyone it took her several hours to make fire on Exile. So they weren't sure why he brought the biggest threat when everyone else was telling Xander that Erika is the biggest threat, and they've been telling him for a while. He also couldn't think of a single social strategy in the final Tribal Council. But all in all, the other players had known for a while that he was a goat, and there were several plans to take him to the final 3 because he was easily beat. This is also not taken from one exit interview. It is taken from many throughout the season.

I just wanted to put that info out there, since it's a stark contrast from what we were shown in the edit. He was not portrayed accurately, which is a little irritating as a fan. Rob and Stephen were speculating that they need a new Ozzy/Malcolm type, so they made him be the fan favorite and the person kids love.

Register on WDWMAGIC. This sidebar will go away, and you'll see fewer ads.